More Titanic trips planned one year after OceanGate sub disaster

[ad_1]

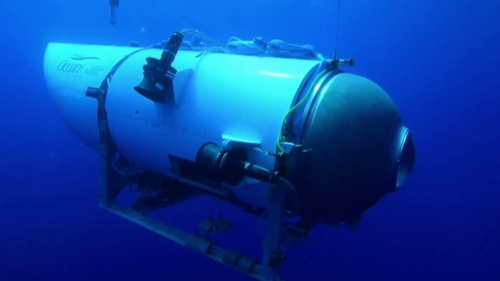

The agonizing spectacle chilled the small but growing community of deep-sea submarine enthusiasts. OceanGate, the controversial operator behind the ill-fated submarine, pulled out shortly after officials revealed the vessel had crashed on its way to the site of the Titanic.

With OceanGate closed for business, the Titanic sub tourism market seems to have shut down.

But instead of destroying the entire industry, the event created an opportunity for subsea system operators to double down on their safety messaging and turn OceanGate into a rogue startup.

One leading sub-operator, eager to demonstrate that the Titan submarine does not meet the industry standards that can make trips to the ocean floor relatively safe, is already planning his own trip to the wreck of the Titanic, where the Titan was headed before it went down.

“If there is anything positive to take from the situation, the legacy will be that there are further investments made in deep-sea submarines,” industry leader Triton Submarines said in a statement.

“I want to show people around the world that even though the ocean is extremely powerful, it can be beautiful, enjoyable and truly life-changing if you do it the right way,” Connor told the WSJ.

Triton, through a spokesperson, told CNN that the trip is in the early stages of planning and that “we can’t share a schedule yet.”

OceanGate, which ceased operations last July, was an emerging but controversial player in the tight-knit world of manned submarines.

But in its pursuit of “increasing access to the deep ocean through innovation,” OceanGate often circumvented regulations and defied industry standards.

In particular, its founder Stockton Rush, who was one of five people killed aboard the Titan, insisted that his unconventional carbon fiber hull was safe, even after experts warned him that it was not as safe as more the expensive titanium used by rivals.

With a brand uncomfortably similar to that of the ill-fated submarine, Triton Submarines has spent the past year trying to differentiate itself from OceanGate.

Two of his main points: 1) OceanGate was a fraudulent operation that skirted regulations and ignored repeated warnings from the tight-knit deep-sea community. 2) The OceanGate subprojects were so experimental that no other commercial subproject would replicate them.

Triton, which counts billionaire hedge fund manager Ray Dalio and filmmaker James Cameron among its investors, has been quick to tout mandates that OceanGate circumvented, such as subjecting its craft to testing by third parties such as the U.S. Bureau of Shipping.

“The deep ocean is no place for compromise,” Triton said in a statement. “By now it should be abundantly clear to everyone that the events in the North Atlantic, the manner in which the operation was conducted and the experimental nature of the ship, have nothing to do with a highly professional, safe and accomplished sector.”

The risk of death is the question

The technology needed to reach the deepest nooks and crannies of the Earth is still in its infancy.

But if the wider adventure tourism industry is any guide, the specter of death will only fuel demand.

Each year, about half the climbers who attempt to climb Mount Everest complete the journey, and at least a few of them die in the process. But somewhat counterintuitively, the deadlier the season, the greater the interest in the following year.

Everest permits have increased significantly in the years since 1996, a season that claimed the lives of 12 climbers and became the subject of international media attention. Last year was also a particularly fatal season, with 17 climbers dying on the route.

This resulted in a 100 percent increase in business for Furtenbach Adventures, an Austrian-based expedition operator.

“Again, it had the effect of Everest getting more attention after this deadly season,” founder Lucas Furtenbach said in an interview.

But he sees a shift taking root from previous years when interest spiked. Lately, he says, “there seems to be more willingness on the part of the customer to pay a premium for higher safety margins. … The statistics show very clearly that the less you pay for your Everest expedition, the bigger the risk of dying.”

This trend toward extra precautions was echoed by Philip Brown, founder of luxury adventure travel firm Brown and Hudson.

In the immediate aftermath of the Titanic’s demise, before OceanGate folded for good, Brown said his company still had a long waiting list for its Titanic tours and that business had even declined.

“The interest is always going to be there in things that push the boundaries,” Brown said in an interview Monday. “But what has happened is that people are much more sensitive to risk, not just in this kind of thing or climbing Everest, but in climbing the charts more generally.”

[ad_2]